If you searched “what is congestive heart failure”, there’s a good chance you’re not doing it out of curiosity. Most people end up here because something feels off — a new diagnosis, a scary symptom, or a loved one using the words “heart failure” like a sentence.

Let us start with the part we say out loud in the ER all the time:

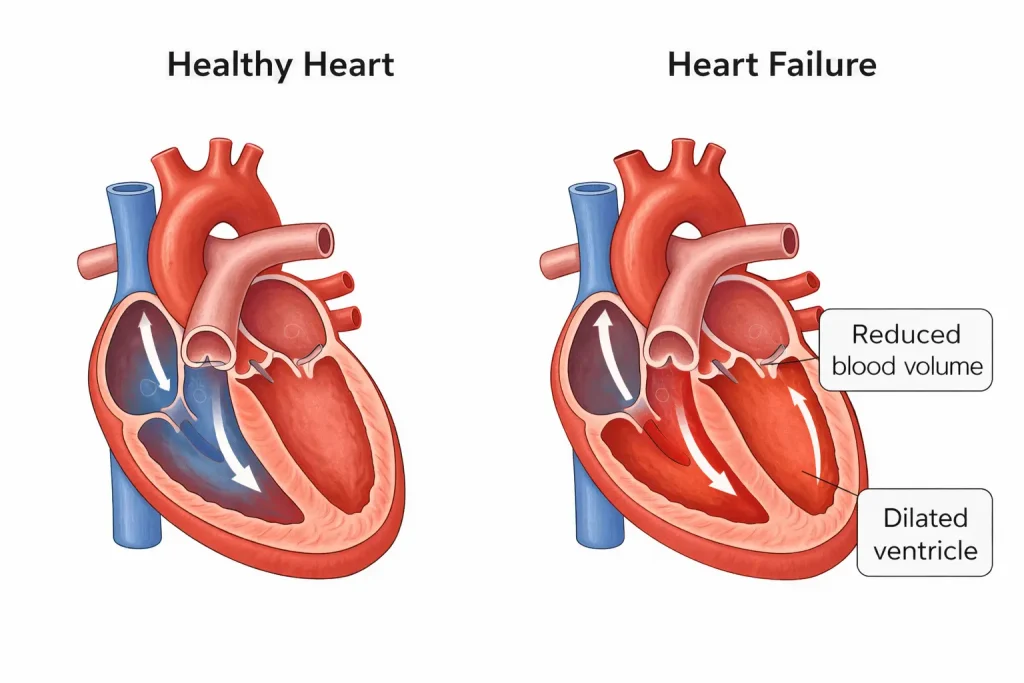

Heart failure does not mean your heart has stopped. It also doesn’t mean you did something wrong. It means the heart isn’t keeping up with the body’s needs the way it should — and because blood flow and fluid balance are connected, symptoms can show up in ways that feel confusing and honestly pretty frightening.

Educational only. This is not medical advice or a diagnosis. If symptoms are severe, rapidly worsening, or you’re concerned, seek in-person evaluation.

The first thing most people misunderstand about CHF

When people hear “congestive heart failure,” they picture a heart that’s about to quit. That’s not how we think about it clinically.

CHF is less about a sudden “failure” and more about a system that’s under strain:

- the heart isn’t pumping efficiently enough, and/or

- it isn’t filling efficiently enough, and/or

- the body is holding onto fluid in ways that create congestion.

That congestion is where many symptoms come from: fluid that backs up toward the lungs, swelling in the legs, a feeling of heaviness, fatigue that doesn’t match what you did that day.

We also want to say this plainly: CHF can be serious, but it’s also often treatable and manageable, especially when the cause is addressed and symptoms are recognized early.

A quick anonymous scenario

A patient comes in from Brazoria County because they’ve been “getting winded” doing normal things — walking from the car, climbing a few steps, laying down at night. They tell us they’ve also noticed their shoes feel tighter and their legs look puffier at the end of the day.

They’re not trying to diagnose themselves. They’re trying to answer one question:

“Is this something I can watch… or something I shouldn’t ignore?”

That’s a fair question. In the ER, our job is to make sure we’re not missing the time-sensitive, dangerous causes — and then to help connect the symptoms to what’s actually happening inside the body.

What congestive heart failure actually means

“Heart failure” is an umbrella term. “Congestive” points to the fluid backup part.

the heart isn’t moving blood forward as effectively as it should, and the body can respond by holding onto fluid. That fluid can build up:

- in the lungs (making breathing harder),

- in the legs/ankles (swelling),

- in the abdomen (bloating, reduced appetite),

- sometimes even as a general “puffy” feeling.

Why symptoms vary so much

Two people can both have CHF and describe completely different experiences:

- one mainly feels short of breath,

- another mainly notices swelling and weight changes,

- another feels fatigue and can’t explain why they “just can’t get going.”

That’s why “CHF” isn’t a symptom — it’s a framework for understanding why symptoms cluster together.

What CHF can feel like in real life

This section matters because most people don’t show up saying, “I think I have heart failure.” They show up describing how their day-to-day has changed.

Breathing changes (the most common reason people come in)

Some people notice:

- they’re short of breath with less activity than usual,

- they can’t lie flat comfortably,

- they wake up at night feeling like they need to sit up to breathe,

- they feel “air hungry,” even if they’re not wheezing.

Not all shortness of breath is CHF — lung infections, asthma/COPD, anxiety, blood clots, and other conditions can overlap. But if breathing changes are new, worsening, or don’t match your normal, we take that seriously.

Fatigue that feels disproportionate

Heart failure fatigue often gets described as:

- “I’m tired, but it’s not sleep tired.”

- “I’m wiped out doing normal stuff.”

- “My body feels heavy.”

Again — fatigue has many causes. What matters is change: new fatigue, rapidly worsening fatigue, or fatigue with other symptoms like swelling or shortness of breath.

Swelling (legs, ankles, sometimes abdomen)

Swelling may show up as:

- sock lines that suddenly leave deeper marks,

- shoes that feel tight at the end of the day,

- ankles that look puffy,

- rings that feel tighter.

Swelling can also come from non-heart causes (kidney issues, liver issues, certain medications, vein problems). But when swelling pairs with breathing changes or unusual fatigue, we think broader and move faster.

Cough or “chest congestion”

Some people notice a persistent cough, especially if fluid is backing up toward the lungs. This can be mistaken for allergies or a lingering cold — and sometimes it really is. But if a cough is paired with shortness of breath, worsening swelling, or sudden exercise intolerance, it deserves a closer look.

What causes CHF (how we think about it clinically)

People ask “what causes congestive heart failure” because they want the “why.” That’s reasonable.

In the ER and in cardiology, we usually think in buckets:

1) Long-term strain on the heart

Conditions like high blood pressure can force the heart to work harder over time. The heart muscle may change — thickening or stiffening — and that can contribute to CHF symptoms.

2) Damage to the heart muscle

Sometimes the heart muscle is weakened or injured by:

- reduced blood flow to the heart (for example, coronary artery disease),

- inflammation of the heart muscle,

- certain toxins (including heavy alcohol use in some cases),

- other medical conditions that affect the heart over time.

3) Rhythm problems

Some rhythm issues can make the heart beat too fast or irregularly for long stretches, which can contribute to failure symptoms or flare-ups.

4) A “trigger” that tips someone over the edge

Even if CHF is already present, symptoms often worsen because something changed, such as:

- a respiratory infection,

- medication changes,

- missed doses of prescribed medications,

- fluid or salt shifts,

- other stressors on the body.

We’re not saying this to put responsibility on the patient. We’re saying it because identifying triggers often helps prevent repeat flare-ups.

How CHF is diagnosed (what each step is trying to answer)

A big reason people search “how is congestive heart failure diagnosed” is because they want certainty. We get that.

Diagnosis isn’t usually one magic test. It’s a combination of:

- symptoms,

- exam findings,

- and tests that point toward (or away from) fluid overload and heart strain.

Step 1: History + exam

We listen for clues in your story:

- What changed?

- How fast did it change?

- What makes it better or worse?

We also look for physical signs of congestion or strain — breathing pattern, swelling, oxygen needs, heart rhythm, lung sounds.

Step 2: EKG (ECG)

An EKG is very useful for rhythm problems and signs that the heart is under stress. But an EKG alone usually does not “prove” CHF. What it can do is help us spot problems that may be connected to symptoms or that need urgent attention.

Step 3: Blood tests (high-level, no “numbers online”)

There are blood tests that can support the picture of heart strain and fluid overload — but they need to be interpreted in context. Other tests help us evaluate kidney function, infection, anemia, and other contributors to symptoms.

Step 4: Chest imaging and heart imaging

Depending on the situation, imaging can help us assess lungs, fluid patterns, and other causes of shortness of breath. An echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart) is often used to better understand how the heart is pumping and filling.

Key point: If you’re trying to self-diagnose from one result — an EKG, one lab, one scan — that’s where misinformation spreads. CHF is a clinical picture, and context matters.

How CHF is treated (and what’s safe to do right now)

People also search “how to treat congestive heart failure” because they want a plan, not a lecture.

Treatment usually focuses on two goals:

- Relieve congestion and reduce strain (help you breathe easier, reduce swelling, stabilize the system)

- Address the cause and reduce flare-ups (long-term risk reduction and stability)

Relieving congestion

Many treatment plans include medications that help the body get rid of excess fluid and reduce the workload on the heart. The “right” plan depends on why CHF is happening and what other conditions are present.

Treating the driver

If high blood pressure is contributing, controlling it matters. If coronary disease is involved, that matters. If a rhythm problem is involved, that matters. CHF management is often about finding and treating the underlying reason, not only chasing symptoms.

What’s safe advice (and what isn’t)

It’s reasonable to do the basics:

- take symptoms seriously,

- don’t ignore breathing changes,

- keep follow-up with your clinician if you’ve been diagnosed.

What we don’t want you doing is:

- stopping or starting medications on your own,

- using online “cure” advice,

- assuming swelling or breathlessness is “just getting older.”

If symptoms are changing quickly, that’s not the moment for internet medicine — it’s the moment for evaluation.

Warning symptoms that shouldn’t wait

If you’re dealing with possible CHF symptoms (or you already have CHF), these are warning symptoms that shouldn’t wait:

- Severe or rapidly worsening shortness of breath, especially at rest

- New or worsening chest pain, pressure, or tightness

- Fainting, near-fainting, severe weakness, or new confusion

- Bluish lips/face or obvious breathing distress

- A very fast or irregular heartbeat with feeling unwell

- Symptoms that are escalating quickly or feel different from your normal baseline

We’d rather you get checked and it turns out to be manageable than wait until you’re in a worse spot.

If you’re experiencing shortness of breath, chest discomfort, new swelling, or symptoms that feel like they’re getting worse — and you’re in or near Angleton or elsewhere in Brazoria County — it’s reasonable to get evaluated. Angleton ER is open 24/7 with board-certified physicians and on-site diagnostics, including lab testing and imaging such as CT, X-ray, and ultrasound, when needed.

Educational only. This is not medical advice or a diagnosis. If symptoms are severe, rapidly worsening, or you’re concerned, seek in-person evaluation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is congestive heart failure (CHF)?

Congestive heart failure means the heart isn’t keeping up with the body’s needs the way it should, and the body may hold onto fluid that can back up into the lungs or cause swelling. It does not mean the heart has stopped.

What causes congestive heart failure?

Common causes include long-term strain (like uncontrolled high blood pressure), damage to the heart muscle (including reduced blood flow to the heart), rhythm problems, and triggers like infections or medication changes that worsen symptoms.

What are the symptoms of congestive heart failure?

Many people notice shortness of breath, reduced stamina, swelling in the legs/ankles, unusual fatigue, and sometimes cough or a congested feeling in the chest.

How is congestive heart failure diagnosed?

Diagnosis typically involves your symptom history, a physical exam, and tests like an EKG, blood tests, and imaging. A heart ultrasound (echocardiogram) is often used to better understand how the heart is functioning.

Is congestive heart failure curable?

CHF is usually managed rather than “cured” in the way people hope the word means. Many people do improve significantly with the right treatment plan and by addressing the underlying cause — but it’s important to avoid internet promises and work with a clinician.

When should someone with CHF go to the ER?

If symptoms are severe, rapidly worsening, or include warning symptoms that shouldn’t wait (like chest pain, severe shortness of breath, fainting, bluish lips/face, or feeling seriously unwell), urgent evaluation is appropriate